I can't seem to stop seeking books by certain authors...

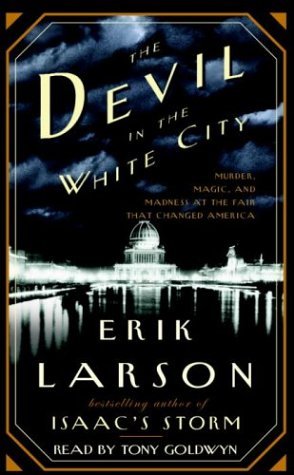

especially when an author is a pro at non-fiction writing. I just finished Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. I had previously read (and not loved, though respected) Larson's Dead Wake, all about the sinking of the Lusitania, and at the end of this past school year, I read In the Garden of the Beasts, which was all about an ambassador in Hitler's Germany (the early years!).

especially when an author is a pro at non-fiction writing. I just finished Erik Larson's The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. I had previously read (and not loved, though respected) Larson's Dead Wake, all about the sinking of the Lusitania, and at the end of this past school year, I read In the Garden of the Beasts, which was all about an ambassador in Hitler's Germany (the early years!).Larson has an interesting alternating style, by which I mean he likes to switch back and forth, from chapter to chapter, from one "side" of the story to another. This has the potential to enliven the pace, but in the aforementioned books, sometimes this only served to drag out incidents that I thought could have been handled more quickly. Certainly, if I had done a tenth of the research that Larson does when writing his books, I would be loathe to cut anything out, but for the sake of moving the plot along, I wonder if more sacrifices could have been made...

With that said, I REALLY liked The Devil in the White City, which also followed the alternating style, although this generally stuck to two storylines, which I thought tightened the focus and made for a more compelling read. (Now, if I was a historian, I might balk at this, as many critics did, but as someone who appreciates a good story, I liked it!)

The premise is that the story follows the development of two men:

|

| Burnham |

architect Daniel Hudson Burnham, the director of the fair and builder of such important structures as Union Station in Washington DC (and, in his lifetime, the tallest building in Chicago), and the serial killer doctor Henry H. Holmes (who had many other aliases), who used the fair to enrich himself and his hunting grounds.

architect Daniel Hudson Burnham, the director of the fair and builder of such important structures as Union Station in Washington DC (and, in his lifetime, the tallest building in Chicago), and the serial killer doctor Henry H. Holmes (who had many other aliases), who used the fair to enrich himself and his hunting grounds. |

| The "White City" of the Columbian Exposition |

Additional factors probably led to my appreciation for this book. First of all, I knew nothing about the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition (i.e. the World's Fair), and I was fascinated by all of the notable people who took part and all of the "inventions" that came of trying to outdo the French, whose previous world fair gave birth to the Eiffel Tower. I also didn't know that the fair built a whole city (painted white, hence the name) within the city, and that these structures, while built by some of the most prominent architects in the USA, were only meant to stand for 6 months! Moreover, I learned a lot about building, business, labor, and medicine at the turn of the century, and how easily standards were set and left unenforced. Finally, in this era of Criminal Minds, its hard not to want to read about serial killers (before people really knew what they were).

Reading this made me want to look up another set of authors I love, Stephen D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner, who wrote the Freakonomics series. I hadn't read When to Rob a Bank yet, as seemed to be more of a "collection" than a coherent book, and I really wanted more of the interesting narrative that I found in the Freakonomics books. However, in listening to the audiobook in short bursts while gardening and cooking, I found that short, blog-like segments were perfect. (And yes, much of the content came from the blog, so you can read much of this and newer content there).

With that said, I agree with many of the reviewers who skewered the book for being too random. It is. But if you, like me, go into reading with the expectation of a serial genre, then the book is a nice injection of Freakonomics into your day. If you are looking for something you can pick up for a while, read some interesting facts, studies, and anecdotes, and then hear Levitt and Dubner's wry and interesting observations, then this is a good book. And, I'll point out, the original Freakonomics series was still a fairly random collection of chapters (albeit longer, more coherently researched chapters), so I'm not sure I'd be trashing the authors for a lack of coherence.

So if you want an in-depth study of the 1893 World's Fair (or anything else for that matter), pick up an author like Larson. If you want some more RANDOM, but just as fascinating discussions, then pick up Levitt and Dubner.